Post #5: Thinking Abdi Nor Iftin's Call Me American

Village Reads is looking forward to hosting our next live “Readers & Writers in Conversation” event with Abdi Nor Iftin, journalist, public speaker, and author of Call Me American on August 10, 2020.

That is about 16 days away from this posting, plenty of time to purchase or borrow a copy and start reading…and thinking!

Fiction and Nonfiction

Nor Iftin’s journey from war-ravaged Somalia to America, defying all odds of survival, is “a memoir” Booklist reviewed “as compelling as a novel.” For those readers who also read Lee Smith’s novella (a short novel!) Blue Marlin, our first VillageReads community read, I hope you are wondering more about what Smith had to say in her afterword “The Geographical Cure” about the difference between fiction and nonfiction:

During a lifetime of writing, I have always felt that I can tell the truth better in fiction than nonfiction. Real life is often chaotic, mysterious, unfathomable. But in fiction you can change the order of events, emphasize or alter certain aspects of the characters—you can even create new people or take real people away in an instant. That means you can instill some sort of order to create meaning, so that the story will make sense—where real life so often does not.

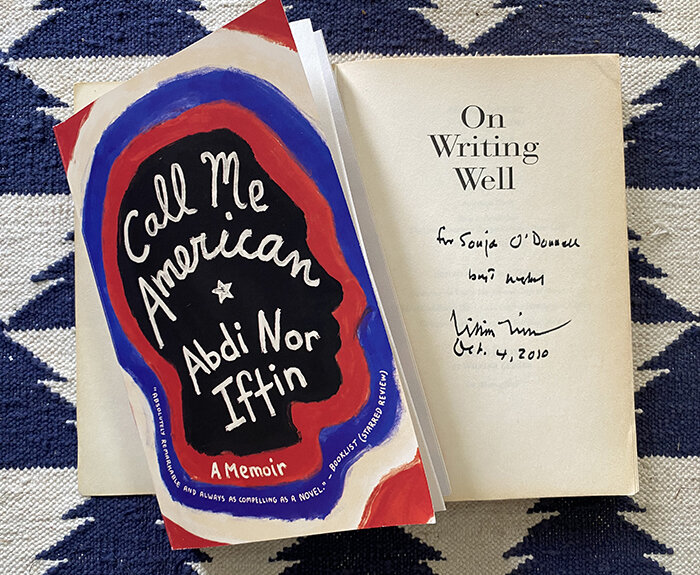

William Zinsser, a formidable writer and teacher of nonfiction, offered in his classic On Writing Well: “Memoir is the art of inventing the truth” (136).

Indeed, both Smith’s novel and Nor Iftin’s memoir are the result of myriad authorial choices, a process that begins with sifting through the shards of recalled experience (memory) and then filling in the blanks. That’s the way I always think about it. In between, in those empty spaces, dwells all the possibility and pain of writing truth.

Words in the Right Order

My father, a research chemist who spent his working life in the laboratory and clearly also at the keyboard writing more than 100 scientific papers, always told me when I’d run to him in frustration over a school assignment that writing was “blood, sweat, and tears.” Odd advice for a kid who simply wanted to be over with it, but one that made more sense over time. I came to understand the nature of my father’s work—the reason he returned to the lab after dinner and often did not return home until early in the morning (well, there may have been a few other reasons for that)—required setting the conditions for a sequence of failures, say, words in the wrong order, before the discovery (eureka) or the prose (words in the right order). This wisdom, if it is wisdom at all, I often shared with my students. Writing is hard work!

Smith and Nor Iftin spent plenty of time in their separate laboratories getting words in the right order, researching their people, places, and times, work that likely involved seeking witnesses, distant relatives, neighbors, notes in old notebooks, facts in newspapers and other available (or unavailable) official (or unofficial) documents, and whenever possible, the special sort of information contained in photographs—a picture is worth a thousand words!

A Writing Lab

If I were to return to the moment of my birth, as Nor Iftin does in the first sentence and paragraphs of his memoir, I’d have to ask my mother, now 85, questions I have never asked her before. Unlike Nor Iftin, I was not born under a tree but in a hospital. That is the only detail, I realize, I possess about that event—Well, I also know the name of the hospital, its location, and perhaps also significantly, as it is in direct contrast with Nor Iftin’s memory, the date of my birth. It is impossible that either of us possesses any actual memory from the day of our birth. At some point in time, we were offered the information, given the memory.

Zinsser explains in On Writing Well that “the secret of the art” of memoir lies in the detail. The detail of my having been born in a hospital probably wouldn’t have been the one I would have selected to begin my memoir had I not paused to reconsider the fact in light of Nor Iftin’s. How would my life have been different had I been born under a tree? Even more, how would that life have been different had that tree been a neem tree? One word, one detail, another story.

Beginnings: Middlesex Memorial Hospital & Under the Neem Tree

I am also left wondering if the detail of my birth in a hospital (Middlesex Memorial Hospital) would have been the most interesting of the many I could have chosen from that day. After my mother, a reliable source, I’d want to find others who were there and who were not there that day. Now that I am thinking about it, I believe I share with Nor Iftin the fact that my father was also not present at my birth. And, I believe I know that he wasn’t even down the road at the local pub, where I understand many mid-century “American” dads (even though mine was also not “American”) spent the hours of their wives’ hospital labor and birthing, a cultural practice of the generation that compares (absent fathers) and contrasts with the Somali (length of time): “[My dad] would stay at his friend Siciid’s place for forty days, the amount of time a woman was supposed to remain chaste after labor” (Nor Iftin 5).

Calling

The direct command of the title Call Me American situates readers in an immediate and intimate space with the narrator-author and simultaneously calls them to consider “American” a space where at least two origin stories may coexist—the reader’s and the writer’s. The very act of calling comes under question. Who gets to be called what by whom and when? More significantly, who gets to be called “American”?

For the baby girl born in a hospital in Middletown, the calling slipped silently through the air and into her lungs, as much an accident of birth as Nor Iftin’s whose calling originated with his friends growing up in Somalia, years before landing on American soil and becoming an American citizen, a comparatively audible “Abdi American.” Indeed, I am now more curious about the effect of where our ears were made, an insight I attribute to an unforgettable passage in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, where he writes in this letter to his young son, “…because my eyes were made in Baltimore…my eyes were blindfolded by fear.” We are coded to hear or not to hear, to see or not to see. The result is a life.

A few readers may have also already culled from their reading memory the famous opening line of American author Herman Melville’s classic work of fiction Moby Dick: “Call me Ishmael.” Its function in this first-person narrative similarly shapes immediacy (here we are now) and intimacy (let’s be friends). In both acts of calling also lingers an uncertainty. Is this the speaker’s actual name, a pseudonym, a desired name…a mask?

Prompting

In your notebook, feel free to take this opportunity write about your beginning. In the “comments” space below, share your thoughts about this process, about writing memoir, and your experience so far “thinking” Call Me American.

Food for Further Thought

But, before I leave this post, I wanted to share two additional supplementary “texts” to accompany our thinking with our new storyteller. One is a warning, the other an invitation—material I have shared again and again:

Nigerian author of the novel Americanah (a wonderful companion read) Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s 2009 TEDGlobal Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story” (now with almost 23M views!)—the opening three minutes here:

And, South African journalist, librarian, editor and educator Hazel Roche’s 1995 essay “Against Borders,” whose concluding sentence reprinted below featured at the head of my course syllabi over the years, an invitation whose impact gains poignancy in these times and with our Village Reads program:

“Reading makes immigrants of us all. It takes us away from home, but, most importantly, it finds homes for us everywhere.”

—Hazel Roche

As with all post, readers are invited to comment below, adding to the conversation. What supplementary texts such as these (a talk, an essay, a poem…) have inspired your reading?